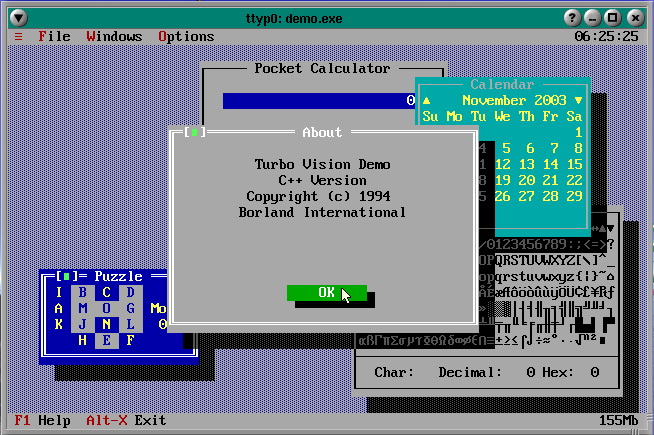

Back in the 80s and 90s on PC, development was basically a free-for-all and as IT businesses started to pop up, various different developers built various different projects. There were some re-usable libraries. I vividly remember a text GUI library called Turbo Vision, which was available for C++ and Pascal in those days.

But, in those days, nothing was fast enough, and the only real way to make your projects shine was to handcraft them yourself, in assembly. Today this is called game engine development, and it only still really happens at that level inside the teams of Unreal Engine, Unity, etc.

In the 90s, when I went to study CS/Physics, I was introduced to UNIX. Or rather its many incarnations like IRIX, SunOS, Solaris, AIX and of course Linux. That was a much more mature world with more powerful computers and better understanding of development. And for standard problems like linear algebra or text analysis, they had battle-hardened libraries dating back as far as the 1950s and 1960s. BLAS (Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms), which is still widely used today, originated there.

But, what they didn’t have was Python, OpenCV, Numpy, etc. like we do today. I worked on a lot of image manipulation and 3D graphics stuff, and there was none of that either. I curated a lot of functionality in my libraries for image manipulation and (the then extremely hip and new) cross-platform development between these UNIX-likes and the Windows PC.

Guido released Python. DOOM came out, later Half-Life and Half-Life 2. Silicon Graphics restarted as Nvidia, the first OpenGL boards became available for Windows PCs. During that era we were still writing most of the graphics stuff ourselves, and we got pretty good at it.

I remember a colleague struggling with a 3D model of a school building, complaining about how this was so hard, slow and expensive, whereas at home Half-Life 2 didn’t seem to have any trouble rendering way more complicated geometry.

The first versions of OpenCV started to appear, and some of the image filtering stuff was a lot better than what we made ourselves. But Windows support for OpenCV on smaller machines was almost non-existant, so it wasn’t very useful in smaller (edge) projects, and we still had to roll our own alpha blending and Sobel filters to analyze the camera image.

More of these libraries appeared. For VR I tried to join in with Aura and VIRPI. Aura was basically Three.js for IRIX, Windows, Linux, AIX, etc. and VIRPI was a VR widget library, where one could click buttons and move sliders while standing in front of them. Ultimately, and like these things always go, nobody else was using these except our team.

As this went on, there was always a dusty professor or an ignorant business guy claiming that “one should never re-invent the wheel”. The science fiction writer Vernor Vinge even predicted that software development would turn into a form of archeology, where a developer would really only dig through mountains of existing code to figure out how to do something (but isn’t that exactly what coding LLMs already do in 2025?).

It’s true. When avoidable, don’t re-invent the wheel. Certainly in a world of hot-headed students who don’t know how to focus properly, or a world of Java developers who are blissfully unaware of the amount of money they waste clogging up corporate IT with giant class hierarchies to describe the simplest business logic.

Code re-use is right when you’re solving generic problems (like parsing, crypto, network, sorting, etc.), when the borrowed library is mature and battle-hardened, the abstractions they use fit your domain, and you really don’t need customization.

Thanks for that statement, ChatGPT…

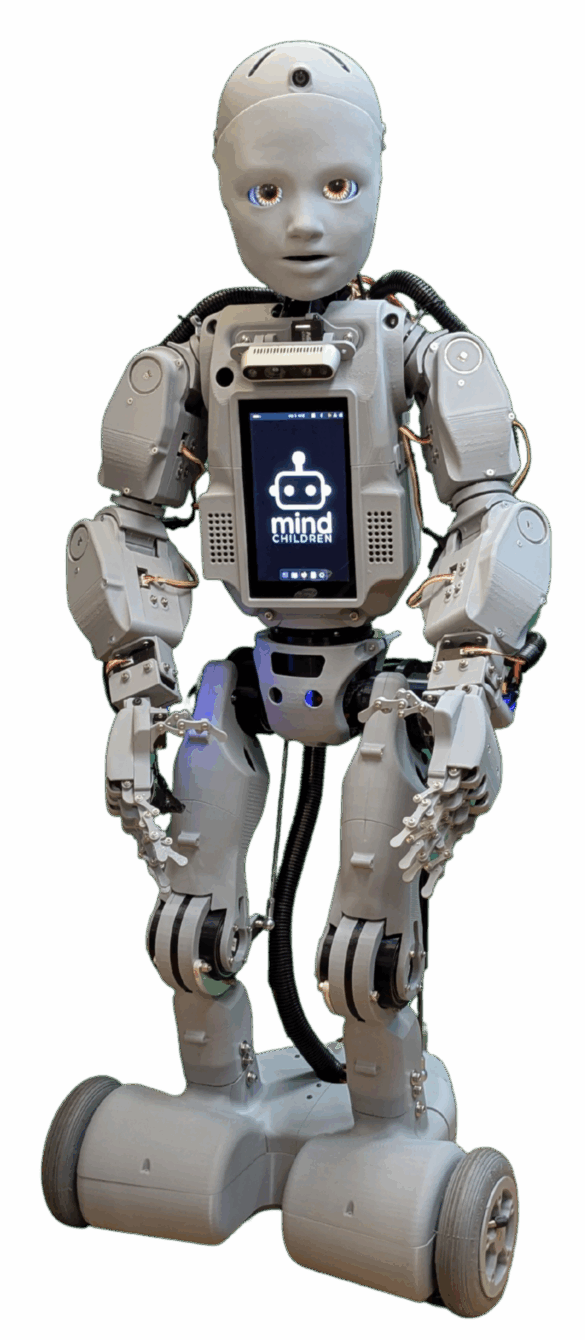

At my current project we’re developing Codey, a social robot. Codey should interact as naturally human as possible in education and hospitality settings. That means, it should make eye-contact, take proper distance, understand body language, communicate with its hands, give hugs and handshakes, understand where everyone is and who is talking, and a whole bunch more.

Of course, one of the key pillars here is a good speech pipeline (speech recognition and generation).

There are tons of libraries that help with this, some more useful than otheres. Some available for offline processing on the robot itself, some requiring the cloud with larger models. Some have different clonable voices. Some have very rich emotional output via SSML. Some are entire pipelines of end-to-end processing via WebRTC with an LLM jammed in the middle (because you really only ever want to build a chatbot on a websites, right?).

Code re-use is not a good idea when you know exactly what you’re doing, and there aren’t really any viable existing solutions yet. Let’s face it. There still aren’t any really good and flexible speech pipelines that allow us total control over what a robot can hear and say and how it says it, including lip sync, facial expressions, hand gestures, etc.

“But have you seen Pipecat?”

Yes, yes, Pipecat is nice, and there are a few other interesting ones, but it’s just not there yet on the level that we want.

Code re-use is also not a good idea when your differentiated value depends on exactly that part of development. We are building a social robot, speech is the primary interface, and we want to have very detailed control over all aspects of the pipeline. We want to be able to experiment with every possible feature imaginable, making sure the robot really comes to life. If our core business relies on the hope that some 3rd party will maybe implement something we think is important, we already lost.

Code re-use is also not a good idea when it forces domain decisions. If a good 3rd-party speech pipeline does appear at some point, but for some reason requires us to use Apple hardware, this would be a big problem. It’s already very difficult with (costly) Nvidia equipment.